And we’ll show you two ways to help. Together, we can be a voice for change and protect Michigan’s land, air, water, public health, and democracy.

Courts across the country, including this one, had been struggling with interpretation of the “sudden and accidental” insurance clause for decades. On a policy basis, some say that holding entities directly liable for pollution damage makes corporations more responsible for preventing pollution from occurring in the first place, because the liablity cannot be passed on to their insurers. Another theory suggests that cleanup and compensation to victims of pollution damage is better accomplished by having insurance money available. See also Upjohn v. New Hampshire Insurance Company and Polkow v. Citizens Insurance, decided the same day.

The City of Woodhaven used chemical pesticides to control insects and pests. The City was sued by a person claiming they had been injured by exposure to the pesticides. The City’s general liability insurer’s policy contained a pollution-exclusion clause. The insurer would not cover the City for releases of pollution that were not “sudden and accidental.” The City’s insurer went to court to get a declaration that it did not have to defend the City or cover its costs in the pesticides lawsuit. The Michigan Supreme Court held that pesticides are included under the pollution-exclusion clause. Thus because the spraying of pesticides was not “sudden and accidental,” the insurer did not have to cover the lawsuit.

The City of Woodhaven used chemical pesticides to control insects and pests. A person sued the City, claiming they were injured by exposure to the pesticides. The City’s contract with its general liability insurer, Protective National Insurance Company of Omaha, included a pollution-exclusion clause. Protective National would only cover releases of pollution that are “sudden and accidental.” Protective National went to court seeking a declaration that it did not have to cover the lawsuit because the pesticide use fell under the pollution-exclusion clause. The trial court agreed, finding that the release was not “sudden and accidental” because pesticide use was part of the city’s normal services. The Court of Appeals disagreed, holding that the pollution-exclusion clause arguably did not apply, because pesticides do not fall within the clause.

Does the City of Woodhaven’s pesticide use fall within the pollution-exclusion clause of its contract with Protective National Insurance Company of Omaha?

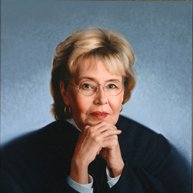

The Court (Justice Riley joined by Justices Boyle, Brickley, Mallett, and Griffin) held that Protective National did not have to cover the lawsuit, because pesticides fall under the pollution-exclusion clause, and the City’s release of pesticides was not “sudden and accidental.” The pollution-exclusion clause of the insurance contract excludes coverage for claims “arising out of the discharge, dispersal, release or escape of smoke, vapors, soot, fumes, acids, alkalis, toxic chemicals, liquids, or gases, waste material or other irritants, contaminants or pollutants.” The Court argued that pesticides clearly fall under this broad definition. Even if pesticides are not technically classified as “pollutants,” they are clearly “irritants” or “contaminants.”

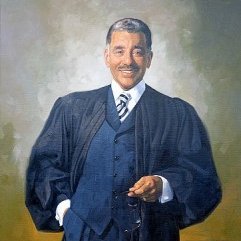

Chief Justice Cavanagh (joined by Justice Levin), dissented, arguing that it is unclear that pesticides are covered by the pollution-exclusion clause. They stated that contract interpretation “must take into account the intention of the parties.” The pollution-exclusion clause, a standard clause in most insurance contracts, was likely intended to exclude intentional dumping of industrial wastes, not the ordinary use of pesticides for pest control.